Shipbuilding was the largest industry in northern Nova Scotia during the 1800s, employing thousands of people from Pugwash to Pictou. When this industry began to fail at the turn of the century the people of the shore communities looked towards the lobster fishery to make their living.

The lobster fishery has changed considerably over the years. It has been the livelihood of the north shore people for the last century. It has suffered through bad times and flourished in good times. For over thirty years hundreds of lobster canneries dotted the coastline of the Northumberland Strait where thousands of fishermen would bring their catches to be processed. These small plants would employ fishermen and cannery workers, both local men and women and those from away. It was a wide-spread and profitable business, but unfortunately short-lived.

With increased technology and new and efficient ways of storing, transporting and marketing lobster, the old canneries were replaced with fewer, larger ones and the lobster fishery was changed forever.

The Very Beginning

Even before the Europeans arrived on the shores to settle in the New World, the Mic Mac (Miíkmaq) and Maleseet Indians of Atlantic Canada had been fishing the seas for lobster for hundreds of years. Long ago, lobsters were so plentiful that they often were found on the beach at low tide, and would wash up on shore in large storms. The tasty crustacean was known as Wolum Keeh to the Mic Macs, and was a source of food, fertilizer, and ornamental material. Hilton McCully wrote in his 1995 book, Pictou Island, in the harbour of Cibou (Sydney, Cape Breton) in 1597, one haul of a little dragnet brought up 140 lobsters. It is quite amazing to think that in just 400 years the lobster population has declined so greatly that if you were to throw a net out now you would be lucky to get any at all!

Long ago, before traps were used, lobsters were fished from the shallow waters by spearing or gaffing. Fishermen hunted for lobsters by torch light on calm evenings, spearing them as they crawled around in search of food. During the day they would spread a slick of oil over the surface of the water darkening the water below, and then throw out cod heads for bait. The lobsters would swarm around the bait and the fishermen would spear them. Although there was no real commercial market for lobster at this time, some fishermen did sell their catch to make money. Because the lobsters were worth more if there were no spear marks in them, the fishermen began using wire cages to trap the animals so they could get a better price. These wire cages were adapted from the Europeans who used them to catch crayfish and Spiny lobsters. There was such an abundance of lobster long ago that it was not a valued commodity and was considered a poor manís food. It wasnít until the second half of the 19th Century that the lobster industry began to flourish.

The Start of the Industry

After the invention of the stamp can in 1847 the process of packing cooked food in hermetically sealed tins for future use spread quickly. New Englanders first canned seafood in Eastport Maine in 1843. It was also New Englanders who were the first successful exploiters of Pictou County lobster. The Boston company, Shedd & Knox built a lobster factory at the East end of Pictou Island in the 1870s. Others soon followed suit.

It was during these early years that the fishermen would row out in dories or in sailboats and set their traps. Two men normally manned a boat and fished about 200 traps. They would set out before dawn and come back to the wharf anytime between 10 and noon. Before the turn of the century the fishermen owned their traps and boats and the rest of their equipment as well, but in later years they would rent it from the canneries that hired them. Fishermen sold their catch by count and not by pound to the packers. For example, forty to fifty cents would be paid to the fishermen for one hundred lobsters, regardless of their size. It was possible for two, hard working fishermen to land four to five tons of lobster a season, from mid-April to mid-summer.

During these early days the industry was not organized or regulated by the government. The government introduced restrictions on the use of soft-shelled lobsters and berried females as well as size restrictions in 1871. A year later they restricted fishing in July and August. Even though there were regulations in place, and the industry seemed to be somewhat organized, the processing part of the industry was still somewhat inefficient.

Before commercial factories became prevalent on the north shore, lobster was processed in fishermenís homes. They would bring their catch back to their houses where their wives would help them boil them in large pots on the stove. The meat would be extracted and then packed in cans that would be fitted with can covers and sealed with a band of solder. Holes were made in the cans where brine would be forced through and then these would be sealed up as well. The cans contained one pound of lobster meat and were packed in cases of forty-eight. It was a process that had a high spoilage rate, but was the only means available to market lobster at this time. In fact, it was assumed that lobster was green in the sea, red in the pot and black in the can.

As the years progressed and the lobster fishing industry changed, the crude and wasteful means of processing lobster in the past were replaced with more sanitary and efficient ways. The number of canneries present in Canada rose from 44 in 1872 to 900 by 1900 and continued to increase through the early part of the century.

The 20th Century

Processing

In the early part of the 20th century there were 10-13 canneries in the River John area. Some of these canneries were Seamanís, Burnaham& Morril, McGeeís, Broidyís and MacLellanís. Local women and those from away would work side by side in the processing room, picking the meat from the shells, washing it and putting it in cans. Money to be made in the lobster factories was considerably better then doing housework. The men at the factories were in charge of boiling the lobster, breaking it apart and in later years, when shipping live came into vogue, were in charge of the live tanks and floating docks. These first small commercial factories packed an average 3, 000 cases (144, 000lbs) during a season.

As the years slipped by, these small canneries began to close down and the lobster processing industry began to consolidate in Pictou, Caribou and Lismore. By the 1930ís the number of canneries had dwindled down to only a handful. One of the ones left, Maritime Packers Limited, turned out to be one of the most successful exploiters of lobster in northern Nova Scotia. .

Over the last 100 years the lobster industry has endured changes in processing, equipment, regulations and fishing methods. Because of these changes, and other various factors, the market for lobster has changed over the years as well. In the early 1900s lobster was considered a poor manís food. Stories told around River John tell of how the children who brought lobster sandwiches to school were considered the poor kids in town. Today many people consider lobster a delicacy. In fact, you have to pay a considerable amount of money to have a good lobster feast these days.

The biggest change that occurred in the lobster market was the development of the demand for live lobster. When people started demanding fresh, live lobster, the lobster processors responded. Soon after shipping live became the norm, different varieties of fresh, frozen lobster meat became available on the market. Quality controlled plants with more efficient packing and shipping methods, as well as high-tech machinery and advanced holding systems, allowed for better products to be developed and marketed. Some examples of the products developed; fresh, frozen lobster tails, vacuum packed whole lobster, fresh, frozen meat in cans, and lobster tomalley and roe. It was gradual changes such as these, which have lead to the development of the industry we have today.

Boats

Not only did the lobster processing part of the industry change throughout the years, but the equipment and gear that the fishermen used changed as well. The sails used to power the fishing boats in the late 1800s and early 1900s were not removed when gasoline engines first appeared in boats around 1910, but remained on board for back-up. The sails were still needed in case the motor broke down, which often happened. Although the motors allowed fishermen to go farther from shore they were very temperamental. The early make and brake engines did not have a clutch and they could not idle. They could go either formal or backwards but had to be stopped completely and re-started to change direction. Most of the boats around the North Shore had Fraser Marine Engines that were made in New Glasgow at the Doc Fraser Foundry.

By the late 1920s fishermen started using car motors in their boats. These motors had starters and could idle. With the advancements made in motorized boats fishermen were able to fish farther, set more traps and therefore make more money. However, even though they had better equipment and were being paid a better price per pound, their costs to maintain their equipment was higher, and the number of people fishing was greater. The standard of living in general increased, pulling the cost of living up with it. So, all in all, the only advantages that arose for the fishermen were those involved with the actual fishing process: they didnít have to use manpower to maneuver their boats. However, they still had to haul their traps by hand and rely on traditional methods of navigation. Electric haulers did not appear in fishing boats until the mid 1900s and radar, Global Positioning Systems, and all other types of electronic equipment did not appear in fishing boats until the 1970ís and 1980ís.

Boats evolved over the years, changing in style, size, strength and speed. With advancements in technology fishermen relied less and less on landmarks to mark their positions, muscle power to haul their traps and self-made gadgets to measure the depth of the water. Not only did the boats they fished on and gear they worked with change, but their lifestyle changed as well. By the 1970ís technology had made the job faster, the day shorter and the work easier. Instead of coming home late in the afternoon fishermen could be home by noon. Today, lobster fishing boats are decked out with radar, colour monitor depth sounders, GPS (global positioning systems), haulers, CBs and radios.

Long ago, before traps were used, lobsters were fished from shallow waters by spearing or gaffing. Fishermen hunted for lobsters by torch light on calm evenings, spearing them as they crawled around in search of food. Although there was not a commercial market for lobster at this time, some fishermen did sell their catch, which was worth more if it bore no spear marks. Switching to a wire cage to trap the lobsters fixed this problem and brought the fishermen a better price.

Not long after the wire cages were brought in, hoop nets became the norm. The rims were made of cast off cart-wheels and netting was stretched over them. These traps were good for shallow water because of the abundance of canner lobsters. (Small lobsters between 1/2 and 1lb). This was beneficial to the fishermen because they were paid per count and not per pound, so the more lobsters that could be caught in the trap the better it was for the fishermen.

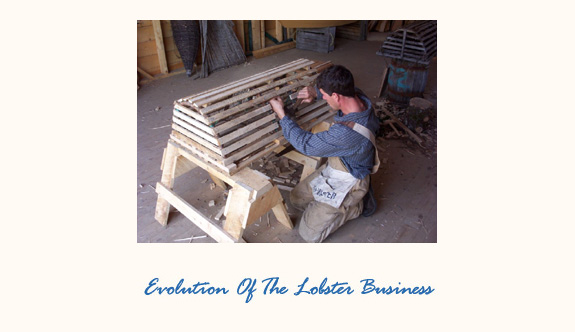

Most lobster traps today are made of metal or a combination of wood and metal and are manufactured in a factory. The original wooden lath trap is said to have originated in Cape Cod in 1810. New England fishermen in the United States used it for years before American companies introduced it to the Canadian fishery through their Atlantic coast canneries. There have been many variations of the lath trap over the years, varying in the number and shape of openings and compartments. There were double headers, three headers, jail, parlor, wheeler and diamond traps.

The traditional wooden lath lobster trap that is still quite common today consists of two main sections, the kitchen and the parlor. A lobster first enters the trap through funnel shaped structures called doors (also called funnels). After successfully entering through one of these doors the lobster enters the kitchen where the bait is tied. When a lobster tries to escape from the kitchen it is led through another door into the parlor. Small vents in the parlor allow undersize lobsters to escape, but larger lobsters are stuck there to await their fate. The doors are shaped in such a way that it is easy for the lobsters to get in but difficult for them to get out.

![]()